FLYHT's JumpSeat

FLYHT's JumpSeat

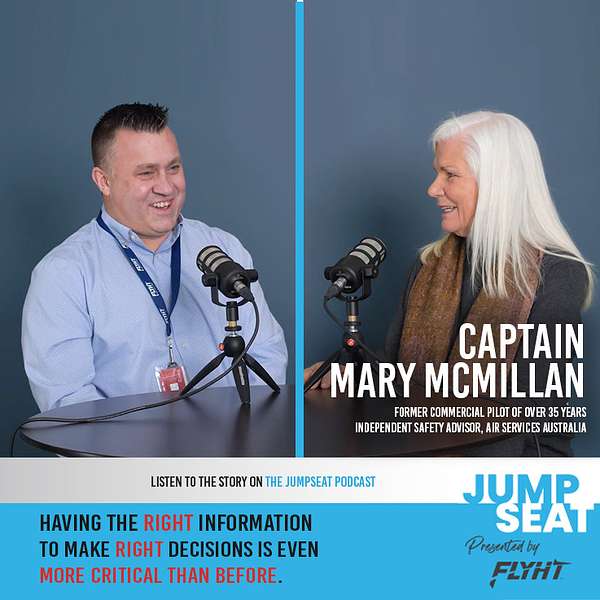

#8: Navigate the Future with Actionable Intelligence — Air Traffic Control and Sustainability with Captain Mary McMillan

New technology is coming into the aviation space, making sure we have the right information to make the right decisions is even more critical than before.

Welcome to this episode of the JumpSeat with host Chris Glass and guest Captain Mary McMillan, former United Airlines Captain and Independent Safety Advisor for the board for Airservices Australia.

In this episode, Mary shares her background and insights on the industry as a engineer, a commercial pilot of over 35 years, and an Independent Safety Advisor. Mary shares her involvement with the industry's transition into RNAV, as well as giving our listeners her insight on the importance for the industry as a whole to have a way of collecting the right information that can be actionable. Monitoring that data will allow us to make good decisions, whether it's new technology or new standards.

Interested in hearing the next episode? Follow us on your favorite podcast platform or subscribe to JumpSeat at www.flyht.com! As this series of the JumpSeat podcast continues, we are always looking to share the most recent and impactful topics to share with our listeners.

Hi, everybody! Welcome back to another episode of the JumpSeat podcast. My name's Chris Glass, I am a Product Owner here at FLYHT Aerospace, and I am with...

Mary:Captain Mary McMillan.

Chris:Welcome to the pod!

Mary:Yeah, thanks Chris. It's great to be here. I would say that you could have been just a little bit more immutable in terms of the weather, it was-4°F(-20°C) when I arrived in Calgary yesterday. And, you know, I'm not quite used to that, but...

Chris:Our very first podcast guest was from Coral Jet, and he was setting up an airline out of Bermuda. And he spent a good three minutes mocking me about the weather outside. And of course, it seems every time we record one of these episodes, there's snow up to my knees. So, welcome to Canada! Welcome to the weather. This is how Calgary is for three or four months out of the year.

Mary:Well, it's great to be here, and the sunshine and the mountains today is just absolutely worth the visit, so it's great to be here.

Chris:Excellent. So, why don't we start by talking about yourself a little bit. Why don't you give me a little bit about your background and what brought you here?

Mary:Well, I took my first wobbly steps at about two and a half. No, back that far, haha. I am actually a member of the Board of Directors here at FLYHT. I've been on the board now, I'm gonna say, close to three years. My background is I was a commercial pilot for over 35 years. I flew mostly international and flew mostly wide-body aircraft. I also have been very active in working in the safety realm for aviation, for both the airlines but also air traffic control. So, I spent some time as the independent safety advisor for the board for Air Services Australia for about four years. So, I had a chance to actually look at how the two pieces actually fit together, both air traffic control and the airlines, and understanding the elements that are critical to making both sides of that equation work is some of the work that I've done that, is most meaningful to me.

Chris:That's really topical right now. As air travel starts to get back to that pre pandemic level, we often think of congestion happening at airports, right? You know, with gates being slot controlled and that kind of stuff, we don't often think about it in the sky, right? But that's a constraint right now that needs to be addressed for what I'm gathering. So...

Mary:Absolutely. I mean, talking about, air traffic efficiency, and increasing the capacity of the airspace is one of the biggest issues of our times, and going forward is going to become even more. So, I think one of the, again, some of the experience that I bring to it as a pilot, one of my first jobs in the airline was as an engineer on the old 747s, the-100s and the-200s. And these were the aircraft that were built by Boeing in the late sixties and really spearheaded long transoceanic flights. And in the old days, those aircraft basically had a navigator who was taking star shots out of the back end of the cockpit. And a radio operator, a couple pilots...

Chris:Like the old Wayfinder days.

Mary:Yeah, exactly. And, by the time I came along, we we'd upgraded to these wonderful carousel INSs that were gyroscopic that we had to have three of them, and at the end of a 10-hour flight, if they were within 25 miles of each other, that was accurate enough. And then we actually saw those airplanes be retrofitted with GPS. So, now we had a way to actually very accurately navigate, but what it did— there was unintended consequence where it actually increased our risk of head on collision. So, we needed a way to actually surveil those aircraft. That was where, companies like FLYHT, and the work that have done in developing communication with those aircraft that are out over oceanic airspace is key and critical. So, it's actually being able to communicate to air traffic control and develop a picture that gives air traffic control that big overview of where that traffic is when it's outside of terrestrial airspace. We saw separation standards actually decrease from a hundred miles in trail across the oceans to now less than 25 miles in trail, depending on the equipment that you have on board. And it actually served to very efficiently increase the capacity of the airspace, going back to the issues that we're going to be working on, in the next few years. We've been able to do that, not only safely, but efficiently. It's been a really eye opening and really revolutionary activities.

Chris:So, moving from, I believe you called it, trailing from..

Mary:In space trailing

Chris:In space trailing from a hundred kilometers or miles?

Mary:Mm-hmm, miles, nautical miles.

Chris:Twenty-five nautical miles. What does that do for capacity? I'm assuming that's, four times greater capacity. Am I correct?

Mary:Yeah. Well, it's even more than that because at the same time we reduced the vertical spacing from 4,000 feet. So, instead of having 2,000 feet above and 2,000 feet below through the reduced vertical space separation, we've been able to bring it down to 2,000 feet. So, we've more than quadrupled the capacity of the airspace for airplanes traveling across any of the oceans, any parts of the world. And of course, where we see the big congestion areas is across the North Atlantic and across the North Pacific. But through technology, through the addition of satellite and some of the information that we're able to actually send to and receive from the aircraft, we've really worked and made tremendous gains both in the economies of the airlines, but certainly the economies of the countries that those airlines serve.

Chris:Well, that can make such a big difference on how much capacity can come into your country and how much economic growth can be there. I'm assuming that process is very methodical to move from 4,000 to 2,000 feet and to move from 100 miles to 25 miles. What goes into that? What's the business case that you need to prove that we can do this safely?

Mary:Yeah, you're exactly right. It's a very methodical, and there's a lot of moving parts to it. And where we're actually taking newer technologies and overlaying it onto existing technologies, and we're taking new aircraft that have some of these capabilities built in and mixing it up with aircraft that have been out there since the 60s. The key to doing that safely is to make sure that you've got all parties involved, that you're coming up with a concept, but you're obviously validating that concept at every step along the way. So, it's been a long process, but we're actually now to the point where we're taking some of that older analog technology that first enabled the reduction of separation standards, and now we're moving it to digital platforms. Which is actually giving us the ability to factor in not only data that we're bringing off of the aircraft or that we're receiving from the air traffic system, but we're also being able to integrate metadata to give us even a broader, bigger picture of, not only what the situation looks maybe within our own little bubble, but how it looks on either side of us and where we're going which allows us to make better decisions.

Chris:And that's really going to help the industry grow in the way— I just see, everywhere I look, there's new airlines popping up here in Canada, we've had three, brand new ULCCs(Ultra Low Cost Carrier) hopping up, adding a lot of capacity into the airspace, finding ways to do more in that space. The very small space is gonna be key to making sure everybody can be competitive in that space. So, it's interesting to see some of the changes coming. You talked about being a commercial pilot... Give me a little bit about that! What was that like? Because it seems like that industry has developed so much over the time, so why don't you tell me a little bit about that?

Mary:Yeah. So, I think the aerospace industry, whether it's airlines or air traffic or rockets or whatever, it's an industry that you're never gonna get tired of because there's always new things happening and different things that are happening and changing, and there's adjacencies to it that make all of this work that can be fascinating. So, I feel like at the end of the day that I've had a very meaningful career, which is very satisfying on a lot of different levels. But as an airline pilot, as I said, I started out my first job as an engineer on the 747s. I actually moved to the copilot seat on the DC-10s. So, I flew some airplanes that are now in the museums. I moved to the right seat of the 747. And then my first captain position was as a captain on 737s domestically. So, I went from flying internationally where things happen fairly slowly to domestic, where...

Chris:Everything is...

Mary:... It's got to happen right now. Yeah. And, we're doing turn times of 45 minutes or less, and things have to happen. And I think one of the ways that I've tried to describe the airline business to people outside the industry is that it really, what makes it work is a full orchestra. I mean, there's music coming from, and people playing from all sides of that orchestra. And it all has to come together, under one conductor in order to make music rather than to just make noise. And certainly an airline is that way. So, things that we make look very simple— I mean, your expectation when you go to the airport is that, regardless of what the weather is out outside, regardless of what it is, where you're going or enroute[that] you're gonna get there on time, your bags are gonna get there along with you, and you're gonna have a pretty smooth experience along the way. And it just takes a lot of people to make that happen.

Chris:One of the things that always shocked me was— Vancouver's a perfect example— I've had the opportunity to be in the bag room and under the wing, is just how long the baggage belts are is what people really don't understand, you know, why does it take 15 minutes for me to get my bag? When you actually see what's going on behind the scenes, 15 minutes is a really good time for that. There's kilometers of baggage belt that need to be maintained and done securely in order for your bag just to get there.

Mary:Yeah. And there's thousands of them that all have to get to the right place. You know, they're all, they're all feeding into different fingers that have to lead to one right place.

Chris:Now, hearing you talk about all the different aircraft you've been on, what's your favorite? I know that's kind of asking like, what's your favorite child, but you've gotta have one that sticks out.

Mary:I think my favorite aircraft was the one I was flying.

Chris:Oh, good. That's a good answer!

Mary:Yeah. So, again, I've flown most of the Boeings, but I also flew the Airbus, the A319, A320, A321. And again, just lovely aircraft. It's kind of a different philosophy in terms of how the pilot interfaces with the aircraft. And, again, just fascinating to see what goes into it and how the engineers make it all work. So, the one I was flying, I think is my answer.

Chris:Yeah, that's good. I'm impartial right now to the Dreamliner myself, but that's just usually because it takes me to places where I could put an umbrella in my drink or hear the Queen speak or something like that— there isn't Queen anymore, but... What routes did you fly?

Mary:So I flew, mostly international. So, I worked for United Airlines, which is obviously a global airline. I have been based on the West Coast, so both, in San Francisco and Los Angeles. I was based on the East coast in New York. A nd I wound up as a 767 captain based in Washington DC. So, we flew a lot of our E uropean flights. we flew into the deep South America on the west coast. We flew the Pacific, m ainly. A nd, I really did enjoy the international flying, mainly because of, o nce you go to a destination city over and over again, you really get to know it. It's not like you're there for two weeks.

Chris:You don't just do the tourist thing.

Mary:Exactly. So you really feel like you get to know the city, the people, the culture, and gain a better awareness about the factors that make up the world around us. So I really enjoyed international flying.

Chris:Yeah, that's one of my favorite things too, is to travel to other countries and to learn about other cultures and learn about how other people do things and it just makes the world a lot smaller of a place for you. I keep a log of how many flights I've taken and how many kilometers I've flown. I'm almost at 800,000 myself, but never been a flight crew or a flight attendant or anything like that. I thought that was a pretty impressive number. But I'm curious, how many kilometers do you think you've flown in the sky?

Mary:I don't measure it in kilometers. We measure it in hours.

Chris:Okay. Hours. So how many hours do you have?

Mary:So, I wound up with a little over 12,000 hours as a commercial pilot.

Chris:Wow. So that must have really helped you when you were dealing with the safety side of it. That much experience really must have translated well into that safety role and changing some of the air traffic control standards and regulations.

Mary:Yeah, it absolutely did. Actually one of the ways that I got involved in both the air traffic side, but also becoming more of an advocate for what we do as opposed to actually there doing it. I was invited to speak at a conference, a nd it was actually environmental conference, and this was in the early days of when we w ere trying to connect the dots between aviation a nd the environment. And I was invited to speak as a pilot that h ad had an experience flying a 757 i nto Dallas. And it was on one of the new approaches, RNAV approaches that had been established, which again, are much more fuel efficient, safer, designed to s ave fuel, d esigned to smooth out the ride, and just bring all of the good things into that we strive for into that aspect of the flight. As we were flying, d escending, I think through about 20,000 feet or so, we were given a runway change and just basically i nserting that information into our f light computer, b asically completely erased the rest of the flight. And so, I described it as, here we are in an airplane built by Boeing with equipment by Honeywell, on an approach designed by the FAA— and with one stroke of the keyboard, we're just kind of lost in space, so to speak. And we obviously have redundancy in order to get that back, but not with the level of precision that is required these days. So, it was, just again, a real reminder that we have to find our way slowly, we have to do it methodically, and we have to ensure that we have all of the players onboard, because what they hadn't factored in is how a pilot would actually use that information, that concerned this one runway change. And now we do.

Chris:This industry's often been accused of moving slowly, but there's a good reason for that because of that safety aspect of it. So you can't just make decisions like a tech industry would or something like that because there's so much that goes into the safety side of it. I'm hoping to do a podcast on RNAV approaches, on its own, but since you brought it up, would you mind talking to our listeners about what that looks like and what that change was? Because I know here in Canada, when it came to some of our Canadian airports, it really helped with our fuel efficiency safety, and it cut down the time that we were in the air. So if you could give me a little bit about that, that would be great.

Mary:Basically, RNAV approach, it's using information, not only that you're gaining from terrestrial flight data sources and navigation sources, but it's actually using information from GPS and instruments that have the ability, not just to tell you where you are, but also to tell you where you are and how high you are and to measure that. And so, in the old days, what we used to have to do is we had what we called step down approaches. So we would fly at a certain level until we reached a point in space that we were beyond some kind of an obstruction, and then we would reduce the power, and then we'd get back down to another level off, and the power comes up until we reached that next step down point. So we were kind of stepping our way down like this. And the reason that we're doing that is so that we're maintaining a safety clearance above either a traffic corridor or we called it"Cumulo Granite". So coming over the Rockies, you want to make sure that you've got a safe margin above any obstructions. But it was also— so it was safe, but it was very fuel inefficient.

Chris:Right. And time consuming.

Mary:And time consuming. Absolutely. As a passenger, you probably experience that where the power comes back and the nose goes down, then the power comes up, and then the power comes back and the nose goes down... So you feel that step down effect. What an RNAV approach does is it actually picks a point in space out here, and it looks at the runway, that's another point in space and it measures and it takes all of those factors into account and actually has a descent point that's going to allow you to bring the power back and then just basically power off until you get to that point on the arrival where you're configuring the aircraft with flaps and gear down and that sort of thing in order to make a safe landing. And it's basically on a three to one glide slope. So it's about a three degree glide slope.

Chris:And you could feel that in the back too as a passenger.

Mary:Very quiet, very calm, very smooth. None of those, appliances that are moving on the aircraft, there's no pitch forward forth.

Chris:Yeah. It's a better experience for everybody. I know when, when we were starting to introduce that here in Canada, there was some resistance and there was a lot of work that had to be done to convince Transport Canada to move forward with allowing this. I'm assuming that work had to be done in the States as well with the FAA. What was that like?

Mary:Well, so again, we wanna make every single flight be that seamless flight from the time that you push back to the time that you actually pull into the gate. So, you know, the ideal flight is that you release the brakes, push back, taxi out, take off, fly your most optimum altitudes, your most optimum power settings. You get to that top of descent point and you pull the power off and you don't touch it again until basically you're ready to touch the wheels down. That's what we're striving for. But you have to remember that at any one time, there's several thousand other of your fellow travelers[doing the same thing]. So actually having information in order to monitor that and ensure that we're integrating the traffic that's going this way, the traffic that's going that way, the traffic that's going this way. We have to be able to integrate that information in such a way that we maintain both the separation standards and a separation standard is making sure that we have a safe space between us that we're not gonna bump into each other. And also try to do it in such an optimum fashion that everybody has that optimum experience.

Chris:That RNAV approach, using satellite technology, being more efficient leads to a greener industry as a whole, and as an industry that burns a lot of fossil fuels, that's where we need to go. So I was wondering if you could kind of give me some insight of where you think the industry's headed when it comes to that greener future?

Mary:Yeah, absolutely. As I said, this was something that I became very interested in about 20 years ago.

Chris:S o w ell ahead of when the industry started to talk about it.

Mary:Well, what the industry was starting to talk about it back then, but just. And trying to connect those dots between aviation and the environment. And we started talking about CO2 emissions and other emissions that come from the burning of fossil fuels, and just the role that that aviation plays in the issue that is now before us is one of climate change. And also, obviously talking about it from an advocacy standpoint is that we all want to make this work, so what can we do in order to achieve a greener future? So aviation was really the first transportation model that actually came up with a plan well in advance— and I mean really is still the only aspect of transportation that has a plan. Maritime is trying to work on it, so is other ground[transport]— trucking, you know, trying to work on it. But aviation has been working on this for over 20 years. It became very apparent to me that this was really the only way that the industry was going to survive and continue to thrive. And this actually kind of brings me to FLYHT too, because what it really depends upon is having this Actionable intelligence and Actionable Information that's going to understand and be able to collect all of these different factors that we've just talked about and make that work, not only just for one airplane or one airline, but for...

Chris:The industry as a whole.

Mary:The industry as a whole. It's a subject that I think, again, as I say, there's a lot of opportunity within aerospace in order to bring any kind of level or interest to it and make a meaningful career out of it. And this is certainly the one for our times.

Chris:Yeah. We had a guest on who works for Connect Airlines in the States, a new airline that's starting up and they have a commitment to using hydrogen fuel. You've seen Air Canada make moves towards electric, and sustainable, renewable fuels. Where do you see that going? What do you see? Do you see a winner in what's next or...

Mary:I don't know if I see a winner in what's next, because again, there's been a lot of activity around, it's called SAF, it's, S ustainable Aviation Fuel. Around the hydrogen, around the electrification, we're going to see a lot o f that coming into this space. And what's going to be even more critical is going to be information to make sure that we have that monitoring information that's going to allow us to do that, a nd make good decisions about what comes next, whether this is usable technology or whether it's not. And there's a lot of challenges. There's been a tremendous lot of progress in the area of the SAFs. We actually have a spec for it. I mean, one of the most important things is that it was a drop-in fuel, which means that an airplane pulls up to the gate, a truck comes out and it's able to drop that fuel in and mix with whatever else is in that tank. Whether it was made from biodegradable, organic material or whether it was fossil fuels. So, I mean, just some of the real elemental pieces of it had to be carefully controlled and monitored i n order to make sure that we got it right. Same thing with electric jets. I mean, we have a lot of regulation, t hat is built around safety of flights. So, w hich determines how much fuel we carry. W e h ave to have enough fuel.

Chris:Extra fuel, alternate fuel, all of that. How do you do that in an electric world?

Mary:How do you do that in Electric world? How much battery do you need

Chris:Taking the cell phone problem to a Q-400?

Mary:Yeah. Exactly. So what's going to be, what are you going to need in order to make that happen? You're going to need information. It'll be key.

Chris:And that's kind of exciting with some of the stuff that I see that we're developing here is using that information to helping our clients make decisions when it comes to especially excess fuel and fuel that doesn't need to be burned on the ground. It's a start, but then the industry's got to go so much further, and I agree, it's going to be information driving that conversation.

Mary:Right. And again, as I said, and as you know, I mean, it's not just about this individual flight, it's about the network as a whole. I mean, there has to be that big picture and then we have to be able to focus down into very, very specifics. And we have to be able to use data in new and imaginative ways in order to make that happen

Chris:Before we finish the pod, I have a question that I ask every guest, because this is an aviation related podcast, and because I like to travel and I like to know where I need to go next— with 12,000 flight hours, you must have seen the globe four times over— where's your favorite place to go? Where should I make the next Glass family vacation?

Mary:Well, I'll tell you, I mean, any place where there's umbrellas in the drinks, that's a good place to start.

Chris:I'm impartial to Hawaii and Tahiti. Those have been two of my favorite places. But, where was the most, I guess, remote place you've been to?

Mary:Well, one of the jobs that I've had in aviation before my airline career was actually ferrying aircraft around the world. So, I've been to some pretty remote places, and some that you would never, ever consider getting to otherwise. But I've spent time on Midway Island, I've spent time on Wake[Island]. I spent time on Christmas Island, which again, were really unique experiences. I've also been to Narsarsuaq and Greenland and some pretty remote places and each — it's kind of like my favorite airplane. I mean, each place that I've visited has its own beauty and its own positives about it. And it always have felt extremely lucky in order to be able to visit those places.

Chris:I would like to end up on Midway Island at some point in my life. I'm not sure it's actually gonna happen, but[I hope]... Mary, thank you so much for spending this time with us today.

Mary:Thanks, Chris.

Chris:I'd like to thank everybody for listening to the JumpSeat. We look forward to bringing you new and exciting podcasts in the future. Thank you.